The drive down CA I-5 from San Francisco to L.A. takes six hours. That’s six grueling hours of negotiating the horrors of urban traffic, trying to stay awake over vast stretches of monotonous Central California farmland, and watching your gas tank guzzle your hard-earned dollars. A plane ride? A nonstop flight would take only an hour and a half, but that’s without considering the time it takes to pass through security or the price of checking in any luggage. In an age where a thought can be sent half-way around the world in mere seconds, this commute is one emphatic no-no to the time-strapped millennial American. Imagine an alternative. What if there was a way to travel this same distance in just half an hour—and for only twenty dollars a ride?

Say hello to the hyperloop.

The summer of 2013, entrepreneur Elon Musk suggested an alternative method of travel: the “Hyperloop,” a proposed form of high-speed transportation with the potential to travel up to 760 mph.1 To put things into perspective, Japanese maglev (magnetic levitation) trains have maxed out at 361 mph, and the commercial Boeing 747 plane travels at an average of 570 mph.2 The speed of sound is 767 mph. On top of it all, while the California High-Speed Rail Project is currently asking for over $68 billion dollars, Elon Musk estimates that constructing the Hyperloop would only cost $6 billion.

Subsonic speeds at one-tenth of the California High-Speed Rail Project—this audacious claim is not a first for Elon Musk, the man behind the Hyperloop. Take a look at his distinctive accomplishments as CEO and founder of the companies PayPal, Space X, and Tesla: today, the online payment service PayPal is ubiquitous; Space X is in the works of delivering its third interstellar manned vehicle prototype; and Tesla’s electric car stocks trade at over $170 a share. Clearly, Elon Musk has been the impetus behind phenomenal and successful ideas. Still, his history of successful ideas does not guarantee that the Hyperloop would be a successful project. Furthermore, Elon Musk has publicly announced that he will not be tackling the Hyperloop. However, he has released a 57 page report detailing his ideas, which are freely available for anyone to view online. Based on this information, let’s take a look at how this project might be able to work.

A brief technical breakdown

If the Hyperloop sounds like something straight out of science fiction, you wouldn’t be far from the truth. Science fiction authors have written about something that sounds very much like the Hyperloop since the 1900s. In addition to its basic design, the proposed technology for the Hyperloop has also been around for many years.

The technology behind the Hyperloop is the implementation of pneumatic action, which relies on the compression of air to induce movement. Starting in the mid-to-late 19th century, numerous major cities in the U.S. and other countries relied heavily on massive underground networks of pneumatic tubes to send mail. Although this technology has been replaced by email, pneumatic action is still at work in post offices and hospitals today. Pneumatic action is also integral to air hockey tables, which utilizes air to reduce friction. In fact, Elon Musk described the Hyperloop as a cross between a railgun, a Concorde, and an air hockey table.1

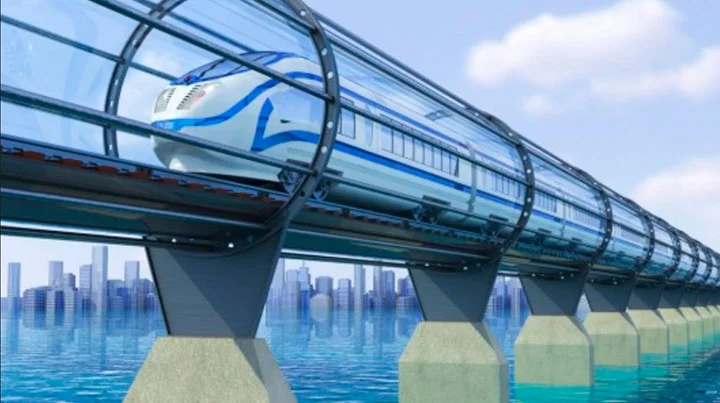

More precisely put, the Hyperloop is a closed-tube transportation system that provides uninterrupted traffic in both directions, perhaps akin to the energy-efficient, tiny maglev pods inside of elevated tubes. This project differs from existing infrastructure developments in three predominant ways by combining a partially evacuated tube with pressure-regulating pods on elevated concrete pylons.1 Though these features are not new, the combination of these attributes is indeed novel.

To carry passengers inside the tubes, two different distinct pod systems have been proposed: The first is an all-passenger version carrying 28 seats. The second, larger system would carry three automobiles and their passengers. No matter which system is utilized, each pod would have pressurized cabins containing backup air supply and oxygen masks in case of emergency, much like an airplane.1

The pods would travel very fast—up to sub-sonic speeds—due to a nearly frictionless journey.1 The steel tubes play an important role by containing a partial vacuum, one ideally one-sixth of the air pressure on Mars. Rather than relying solely on electromagnetism for the entirety of the trip, friction would also be greatly reduced thanks to electric compressor fans attached to the traveling pods.

The electric compressor fans can help overcome the Kantrowitz Limit, a limitation on mass flow related to the size ratio between pod and tube. If the space between a pod and the interior of the tube is too small, then the Hyperloop system will behave like a syringe, where the pod will push the entire column of air in the tube. The compressor fans address this problem by pushing high pressure air from the front to the rear to create a cushion of air underneath the pod.1

To lower energy costs on the environment, the bulk of the system would be powered by a solar generator. This solar energy would be split between charging the pod batteries and the rest of the system. Musk’s plan would rev up the pods from their stations using magnetic linear accelerators resembling railguns;1 once in the main travel tubes, the pods would be given periodic boosts by external linear electric motors similar to those in the Tesla Model S.

Finally, in order to lower the cost of construction, the partially-evacuated tubes would be elevated on concrete pylons. This type of system mitigates damage caused by earthquakes and reduces maintenance costs.1 Additionally, elevation would allow the Hyperloop to travel without interruption, bypassing ground traffic, farmland, and wildlife. By building on pylons, the system could also follow the California I-5 highway, reducing the need for expensive land acquisition suits.

Again, these suggested attributes for the Hyperloop already exist in one form or another, but they have not yet been combined in such a manner. For instance, much of the Federal Highway System uses concrete pylons to elevate interwoven freeways. The subways of New York City and Chicago are enclosed systems, but they do not run on cushions of airs. Maglevs run on a cushion of air, but they are not enclosed.

So what does this mean?

All in all, the scientific community generally seems to agree that the Hyperloop is technically feasible. However, Elon Musk’s proposal does come with many caveats. The most significant problems seem to stem from economic and political concerns. Critics have claimed that Elon Musk’s idea is overtly conceptual and utilizes unrealistic cost estimations. The estimations are particularly contentious because the Hyperloop proposal is reminiscent of the California High-Speed Rail, a project with initial estimates that were much lower than the current budget; in 2008, state voters had approved $9.91 billion dollars for the California High-Speed Rail Project. By April 2012, High-Speed Rail estimates had reached $91.4 billion, nearly ten times original estimates, before public outcry triggered a budget revision.

However, the Hyperloop manages to avert many of the same issues plaguing the California rail project. One benefit of building on concrete pylons is a reduction in land acquisition, currently the most expensive and politically contentious issue affecting transportation projects. Another benefit of the project is an independence from federal funding. Without a reliance on bond measures or public coffers, the Hyperloop would not need to build in potentially unprofitable areas to keep policymakers satisfied. Free from political strings, it could focus on creating a profitable, sustainable venture.

Regardless of the advantages, it seems unlikely that construction on the Hyperloop following the proposed route between San Francisco and Los Angeles would begin during the construction of the California High-Speed Rail. This is unfortunate, as a route between L.A. and San Francisco guarantees a customer base. Furthermore, city pairs that are 120 to 900 miles apart are ideal for rail or similar transportation, as this distance is too far to comfortably travel by car and yet too close to efficiently travel by plane.7 L.A. and San Francisco fit perfectly in that niche.

Elon Musk has not made any plans to develop the Hyperloop, causing many to believe that the entrepreneur may be using the Hyperloop as an elaborate red herring. One critic has pointed out that the construction of the California High-Speed Rail would directly compete with automobiles in Silicon Valley, one of Tesla’s target market demographics. Could Musk trying to derail the already tenuous rail initiative in order to reduce economic competition? Interestingly, after the official Hyperloop press release, local politicians in the Silicon Valley area lobbied to prevent the California High-Speed Rail from developing in their respective constituent zones. Was this mere coincidence?

Regardless, the most valuable attribute of the Hyperloop project is its status as an open-source engineering project open to privatization. Using the same basic principles, one man has even built a working miniature prototype with the capacity to hover on a cushion of air. Autodesk, a 3D design software, has produced realistic, promotional renderings of the Hyperloop. ET3 is a company that is working on similar evacuated vacuum tube designs.3 In this day and age, crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter and microfunding organizations like Kiva could potentially be used to financially support the construction of the Hyperloop. In the Netherlands, the company Windcentrale raised over 1.3 million Euros in only thirteen hours from 1700 Dutch households eager for a local wind turbine.5 Money for the Hyperloop could be similarly raised.

Whatever the case, one thing is clear: even if the Hyperloop remains a conceptual project, the idea has opened up an important dialogue regarding the future of mass transportation in America. It has bought attention to the inefficiencies of the California High-Speed Rail Project, and it has renewed interest in technological advances for public transportation. The Hyperloop might also lead the U.S. towards privatized or crowdfunded infrastructure. Perhaps most importantly, the buzz around the Hyperloop has reaffirmed the need for alternative transportation.

References

- Musk, Elon. Hyperloop Alpha. https://www.teslamotors.com/sites/default/files/blog_images/hyperloop-alpha.pdf (accessed Oct 20, 2013).

- 747 Family. http://www.boeing.com/boeing/commercial/747family/background.page (accessed Nov 4, 2013).

- “The Evacuated Tube Transport Technology Network.” ET3, 24 Oct. 2013. <http://et3.net/>.

- United States Bureau. The California Energy Commission. California Gasoline Statistics & Data. Energy Almanac. Web. 30 Oct. 2013. <http://energyalmanac.ca.gov/gasoline/>

- “Dutch Wind Turbine Purchase Sets World Crowdfunding Record.” Renewable Energy World. Ed. Tildy Bayar. 24 Sept. 2013. Web. <http://www.renewableenergyworld.com/rea/news/article/2013/09/dutch-wind-turbine-purchase-sets-world-crowdfunding-record>.

- “2012 Annual Urban Mobility Report.” Urban Mobility Information. Texas A&M Transportation Institute. Web. 11 Oct. 2013. <http://mobility.tamu.edu/ums/>.

- “Competitive Interaction Between Airports, Airlines, and High Speed Rail.” Joint Transport Research Centre. Paris. Discussion Papers.7 (2009): 20. 8 Dec. 2013.

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2013. <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/theworldfactbook/>.

- Levinson, David. “Density and Dispersion: the Codevelopment of Land use and Rail.” London Journal of Economic Geography, 8 (1), 5577. 10.1093/jeg/lbm038. 2007.